In almost all of my presentations, no matter the topic, there’s a singular spoken line that jars people’s perceptions of disability…

“I was born into a world that wasn’t designed for me.”

And I’m pretty sure President Roosevelt, diagnosed with Polio and a chair user in the 1920s, experienced this even more. With each generation between then and now, advocates and change makers have rallied for “inclusion.” Because of its personal and collective interpretation, progress has occurred.

And I’m pretty sure President Roosevelt, diagnosed with Polio and a chair user in the 1920s, experienced this even more. With each generation between then and now, advocates and change makers have rallied for “inclusion.” Because of its personal and collective interpretation, progress has occurred.

This week marked the 32nd anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). While America is celebrating the important work of the 1990 Act, I dare you to imagine a world where you must constantly fight for your essential rights to access the world around you…at home, work, in leisure activities, and even, literally, on the street. Being seen and heard is the essence of feeling valued and included as human beings, but that can’t occur without equal access to opportunity.

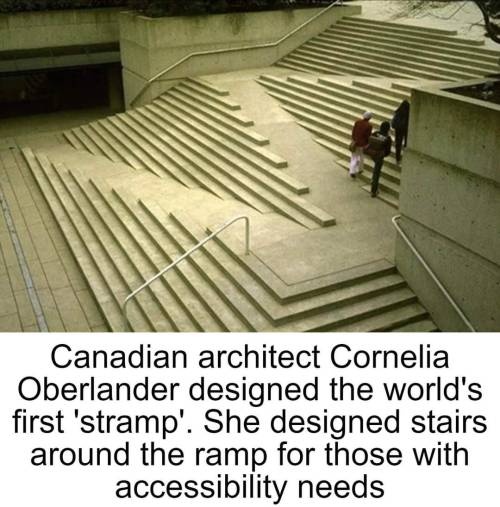

What comes to your mind when you think of accessibility? More often than not, accessibility is associated with the physical environment — the ability to access crosswalks, doors, elevators, lights, buildings, etc. Most design concepts are based on the assumption of physical “normalcy,” where adaptations are an afterthought. Rather than accessibility being treated as a separate component that tends to single out the disability community, could accessibility be the new “normal” for all? Universal Design is considered just that – the mindset where everyone can access their environment without adaptations. Increasingly, the design and build communities have come to rely on its features for commercial and residential applications.

Now if we look past what is visible, accessibility is ultimately an equalizer for everyone in all aspects of society. The crux of the ADA is to minimize the physical barriers by allowing people with disabilities to have physical access to the environment. I suggest we are beyond the concept that people with disabilities should be allowed” to access the same environment as the able-bodied person. If our mindset stops there, we are already behind!

How can we as a society plan for fuller inclusion? It starts with continuous innovation, of course, but also perspective. That means listening to real time experiences of living with a disability. Our goal at Fearless Independence is to lend inclusionary expertise to businesses that are willing to listen without limits and want to build a future designed for everyone.